Clarence Thomas’s Friend of the Court

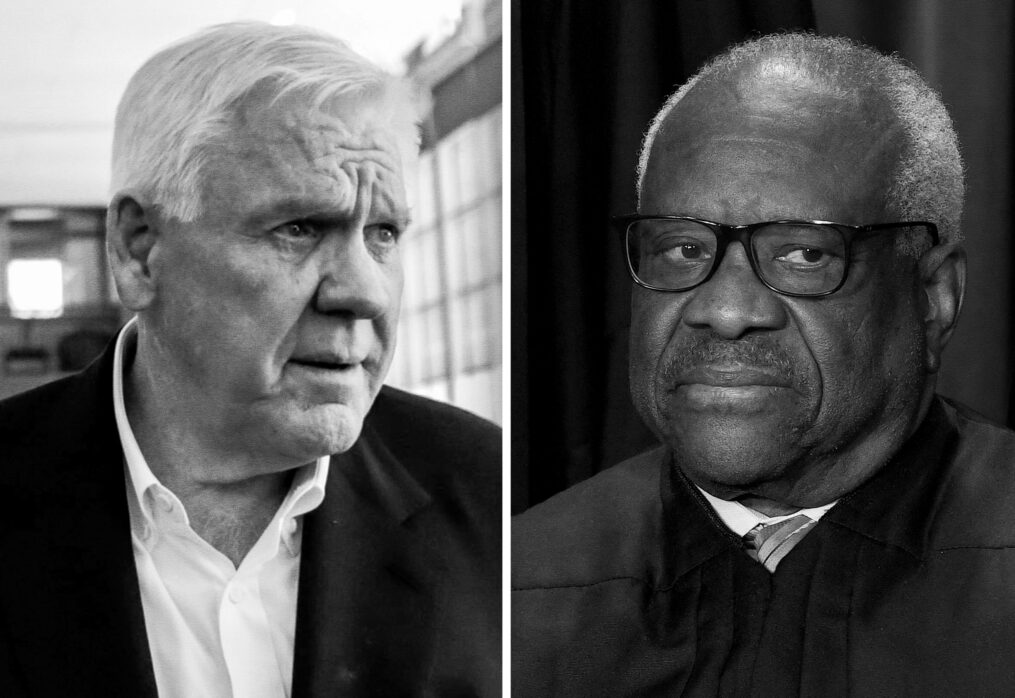

Every year, judges and Justices release information about their finances. Under a rule designed to maintain public trust in the courts, disclosures must include any gifts worth more than four hundred and fifteen dollars, as well as bonds, stocks, and other assets valued at more than a thousand dollars. When ProPublica reported earlier this month that Justice Clarence Thomas had failed to disclose opulent trips funded by a conservative billionaire, Harlan Crow, the Justice denied violating the rule. Thomas explained in a public statement that Crow and Crow’s wife, Kathy, were among his and his wife’s “dearest friends,” and that he had been advised that “personal hospitality from close personal friends” need not be disclosed.

A statement from Crow twinned Thomas’s. Crow said that he and his wife had been “friends with Justice Thomas and his wife Ginni since 1996,” that the two couples were “very dear friends,” and that the Crows were fortunate to have a “great life of many friends.” Crow claimed that he never talked about Supreme Court cases with Thomas or tried to influence him “on any legal or political issue.” He was also unaware of anyone else doing so on their trips. “These are gatherings of friends,” he said.

The defenses shared a crutch. Like notes scrawled at the end of a yearbook, they invoked friendship over and over, sometimes twice in a sentence. The incantations seemed designed to show that Crow’s gifts were hospitality, which, as Thomas claimed, would not have needed to be disclosed. Yet many experts understand that exception—defined in the law as food, lodging, or entertainment—not to include the jet flights, island-hopping yacht trips, and exclusive retreats that Crow gave Thomas.

The rule on financial disclosure is one of the few that bind Supreme Court Justices. Other federal judges follow a code of conduct with both specific and broad constraints. The code bans political endorsements and tells judges to act in a way that avoids the “appearance of impropriety” and promotes “public confidence in the integrity and impartiality of the judiciary.” Efforts to hold the Supreme Court to similar standards have so far failed, but the Senate Judiciary Committee has achieved more modest steps. It has, for instance, pressured the agency that interprets the financial-disclosure rule to clarify the “hospitality” loophole that Thomas is now invoking. Last month, the agency put out new guidance that specifically tells judges and Justices to disclose trips on private jets and nights at resorts that are gifted to them. (Thomas said, in his statement, that he would comply with the new guidelines.)

Even if Thomas’s defense is fallacious, it was apt: the Court has often inspired a strange and almost fetishistic fixation on friendship. The closeness of Antonin Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, despite their opposition on legal issues, is so famous that it inspired an opera. The libretto’s main duet, “We Are Different. We Are One,” features the lines: “Sep’rate strands unite in friction / To protect our country’s core.” The two Justices indeed watched operas, celebrated New Year’s Eve, and spent time in India together—events that have been rehashed in many articles praising a relationship that transcended ideology.

In the past few years, as the Court has battled loudening claims of illegitimacy, friendship has stayed a common refrain. At oral arguments for Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, Justice Sonia Sotomayor asked whether a Court that took away abortion rights could “survive the stench” of partisanship. The same could have been asked last spring, after text messages showed Clarence Thomas’s wife, Ginni Thomas, conspiring to keep President Joe Biden out of office. But, at a convention last spring, Sotomayor took a different tone than she had in the Dobbs arguments. She encouraged the audience to believe in the judiciary and singled out Justice Thomas as someone who “cares deeply about the Court as an institution.” The two of them shared a common understanding about “people and kindness,” she said, which was why she could be “friends with him” despite their “difference of opinions in cases.”

In January, 2022, after NPR reported that Sotomayor was joining arguments remotely because her neighbor on the bench, Justice Neil Gorsuch, was refusing to wear a mask, the two put out a joint statement. They reassured the public that, though the two may “sometimes disagree about the law,” they were “warm colleagues and friends.” Around the same time, Justice Stephen Breyer announced that he would retire. Each of the remaining members of the Court put out a statement, and all but Justice Samuel Alito’s referred to Breyer as a friend, a “dear friend,” or the “best possible friend.” (Alito’s tribute was also warm and called the retired Justice “friendly.”) Justice Thomas’s said that he loves him.

There is ritual in these shows of camaraderie. The Justices seem to hope that waving their unlikely friendships around like bundles of sage will rid the Court of its partisan “stench.” If Sotomayor thinks Thomas is upright and principled, rather than a right-wing ideologue, maybe we should, too. If Ginsburg stayed close with Scalia even after he witheringly dissented from her majority opinion, in United States v. Virginia, that it was unconstitutional to exclude women from a military academy, then he must not have been sexist, or at least not intolerably so.

But too much has been made of the Justices’ friendships—just as Justice Thomas wants us to make too little of his with Crow. Collegiality does not take the place of oversight. There is essentially no mechanism to enforce even the relatively limited ethics rules that the Justices must follow, and which Thomas now appears to have broken. Under the fiction of judicial friendship, as long as the Justices have faith in one another, so must we all have faith in them.

If Thomas’s failure to disclose his lavish trips with Crow was only ambiguously unethical, newer revelations are more clear-cut. According to a report last Thursday by ProPublica, one of Crow’s companies bought three properties from Justice Thomas and his family in 2014. Thomas’s mother still lives in one. Despite rules that require federal officials to disclose most real-estate sales that are worth more than a thousand dollars, the Justice reportedly did not divulge the deal. (Thomas did not respond to ProPublica’s questions about the properties’ sale.)

Shortly after ProPublica’s first story, Senator Dick Durbin said the Judiciary Committee, which he chairs, would act. A few days later, he sent a letter to Chief Justice John Roberts, announcing that the committee would hold a hearing. It urged the Chief Justice to do his own part by opening an investigation and taking “all needed action to prevent further misconduct.” What form that action could take is hard to imagine. Probing Thomas’s potential misconduct would fray the trust that binds the Justices, but doing nothing would further erode the public’s trust in them. On Thursday, in a new letter citing “a steady stream of revelations regarding Justices falling short of the ethical standards,” Durbin asked Roberts or another Justice of his choice to testify at the committee’s hearing, which will be held early next month. If he accepts the invitation, Roberts might have to decide what a friendship is worth. ♦